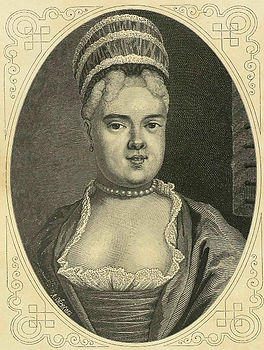

Elizabeth Petrovna (1709 - 1762)

Elizabeth Petrovna as a child

by Ivan Nikitin in 1713

Anna Petrovna and Elizabeth Petrovna

by Louis Caravaque in 1717

Elizabeth Petrovan was born on 18 December 1709 at Kolomenskoe, near Moscow - the day her father, Peter The Great, arrived back after his astonishing victory over the Swedes at the Battle of Poltava. As far as the world knew, Elizabeth was illegitimate; her father said that he had 'not found the time' to publicly marry her mother, Martha Skavronskaya, renamed Catherine. In fact, in November 1707, Peter had married Catherine in private, but the secret was kept for reasons of state. On 9 February 1712, Peter married Catherine again, this time with public fanfare, when the guests were treated to an amusing spectacle. As the bride and the groom walked round the lectern, they were followed by two pretty little girls, wearing jewels in their hair and clutching at their mother's skirt. This was the three years old Elizabeth, accompanied by her sister, four years old Anna.

On 28 January 1722, when Peter decided thirteen years old Elizabeth to be of age, she was fair-haired, blue-eyed, brimming with energy and health. She delighted everyone with her laughter and high spirits - an opposite to her more sedate sister, whom she worshipped. Both Anna and Elizabeth received the full education of European princesses: languages, manners and dancing. They learned French as well as Russian and Anna, the better pupil, also learned some Italian and Swedish. Elizabeth recalled the keen interest her father had taken in his daughters' education. He came frequently to their rooms to see them and asked what they had learned in the course of the day. When he was satisfied, he praised them, kissed them and sometimes gave each a present.

At fifteen, Elizabeth was not as tall and stately as her sister Anna, yet there were many courtiers who preferred the radiance of the lively blonde to the grace and majesty of the statesque brunette. And though she was still shy in the company of boys, Elizabeth was considered ready for marriage. From the time of Peter's visit to Paris in 1717, the tsar had hoped to marry Elizabeth to Louis XV, who was two months younger than her. Elizabeth had been schooled with this marriage in mind. She was taught the French language and the French court manners along with the French history and literature. Yet despite the recommendations of the French ambassador and the girl's manifest charms, at Versailles her credentials were tarnished: her mother was a peasant and the daughter may have been born out of wedlock. Thus Peter's hope for Elizabeth was thwarted, but one of his two daughters was to marry.

In 1721, when Elizabeth was not quite twelve and Anna was thirteen, Duke Karl Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp, the nephew of Peter's legendary adversary Charles XII of Sweden, had come to St Petersburg. Peter welcomed the young man with a pension and a place of honor. To further advance his own cause, the duke began to pay court to Anna. Four years later, when Anna was seventeen - and despite Anna's lack of enthusiasm for this suitor - the couple were betrothed in a service in which Peter himself took rings from each partner and exchanged them with the other. On 22 November 1724, their marriage contract was signed, by which Karl Frederick and Anna renounced all rights and claims to the crown of the Russian Empire on behalf of themselves and their descendants. However, there was a secret clause allowing the tsar to name a successor out of any sons from the marriage.

A few months thereafter, on 28 January 1725, Peter The Great fell ill and died. The wedding was postponed while her mother assumed the throne as Empress Catherine I. On 21 May 1725, a grand wedding was held for Karl Frederick and Anna in the Trinity Cathedral. After the ceremony, the wedding party crossed the River Neva to the Summer Garden, where a special banqueting hall for the occasion had been designed. The tables were set with all sorts of delicacies, including enormous meat pies. When the orchestra began to play, the dwarves jumped out of the pies and began to dance on the tables.

Her father's death profoundly affected Elizabeth's future. The prospect of a great match for Elizabeth became remote. Her mother still hoped for a French marriage, but Louis XV had married the Polish princess, Marie Leszczynska, a daughter of Stanislaw I of Poland and Catherine Opalinska. At this point in St Petersburg, Elizabeth's new brother-in-law began praising the merits of his twenty years old cousin, Karl Augustus of Holstein-Gottorp, who happened to be brother of Johanna Elizabeth of Anhalt-Zerbst, mother of future bride to Peter III. Catherine I, who was fond of her son-in-law, agreed to invite this second young Holstein nobleman to Russia. Karl Augustus reached St Petersburg on 16 October 1726 and made a favourable impression. Elizabeth saw him as the kinsman of her adored sister's husband, which made it easy for her to fall in love. The engagement announcement had been set for 6 January 1727, when Empress Catherine I was stricken by a series of chills and fevers. The ceremony had to be postponed until she recovered. However, the empress did not recover; instead, she grew worse and in April, after reigning only twenty seven months, she died. In May, only a month after her mother's death, Elizabeth decided to go ahead with her marriage. Then, on 27 May, her prospective husband was stricken and several hours later the doctors diagnosed smallpox; four days later he was dead. Elizabeth, her happiness shattered at seventeen, cheriched his memory for the rest of her life.

Catherine I's death in May 1727 made Duke Karl Frederick's position precarious, as the power shifted to the hands of Alexander Menshikov, who aspired to marry eleven years old Emperor Peter II to his own daughter, Maria. And a quarrel between the troublesome duke and Menshikov resulted in the former's withdrawing to Kiel on 25 July 1727. When they arrived in the capital of Holstein, Karl Frederick underwent an instant personality change. Merry and gallant in St Petersburg, he was now a rude and drunken boor. He spent his time in the rowdy company of friends and other women, leaving his wife, now pregnant, entirely on her own. In Kiel, Anna would spend her days writing long, tearful letters to her sister Elizabeth. On 21 February 1728, Anna gave birth to a son named Karl Peter Ulrich, the future Peter III. A few days after the birth, the barely twenty years old duchess caught puerperal fever and died on 4 March. Before her death, Anna had asked to be buried alongside her father in St Petersburg. Thus two ships were dispatched to Kiel for Anna's body; the coffin was transported up the River Neva and, on 12 November 1728, she was laid to rest next to her parents.

Elizabeth was left alone and ever since her parents died the nobles of the realm suddenly seemed to have less time for her and the limelight that had always followed her faded right away. Her mother had left her two country estates and the house at Tsarskoe Selo, so she was materially provided for. She had her own household and her own staff, but life which had always been so easy for her suddenly became difficult and even dangerous. Although, by her mother's will, she now was next in line to the throne after Peter II, she posed no political threat to the young emperor. Indeed, she turned to him for friendship and soon Elizabeth and her nephew - a handsome, physically robust boy, tall for his age - became companions. Peter enjoyed his aunt's beauty and bubbling high spirits and liked having her nearby. In March 1728, when the court moved to Moscow, Elizabeth accompanied him. She shared the emperor's passion for hunting and together they galloped through the hills of Moscow countryside. In summer, they went boating together; in winter, sledging and tobogganning. When the emperor was away, Elizabeth sought other male companions. She confessed that she was 'content only when she was in love' and there was talk that she had been generous in giving pleasure to the young Peter himself. Elizabeth was endowed with her father's ardent impetuosity and never hesitated to gratify her desires. She was unashamed; she told herself that she had been made beautiful for a reason and that fate had robbed her of the only man she had ever really loved.

Elizabeth remained indifferent to power and responsibility. The friends who urged her to take more interest in her future were turned away. Then, there was a moment when the throne itself seemed there for the taking. On the night of 11 January 1730, fourteen years old Peter II, dangerously ill, died of smallpox. Elizabeth, then twenty, was asleep nearby. Her French physician, Jean Armand de Lestocq, burst into her bedroom, saying that if she arose, presented herself to the Guards, showed herself to the people, hurried to the Senate and proclaimed herself an empress, she could not fail. However, Elizabeth sent him away and went back to sleep. By morning the opportunity had evaporated and the Council had elected her thirty-six years old cousin, Anna Ivanovna. Elizabeth's failure to act was based partly on her apprehension that if she moved and failed, there was the chance of disgrace or even imprisonment. The stronger reason was that she was not ready. She did not want power and protocol; she preferred freedom. And she never regretted that night's decision.

Empress Anna was always wary of Elizabeth. Concerned that her cousin might constitute a threat, she took Elizabeth aside when the younger woman came to pay her respects. But Elizabeth's cheerful, open replies partially convinced the empress that her own fears were exaggerated. At first, Elizabeth was expected to attend the court on formal occasions and sit demurely near the empress. Elizabeth did her best, however, nothing could prevent her outshining her imperial cousin. Eventually, she wearied of the strain of living at the court and retreated to a country estate, where she resumed her independent life and where her behaviour and morals were free of the court surveillance.

Elizabeth loved the countryside, with its primeval forests and wide meadowlands. She loved joining in the lives of the peasants and shared their amusements such as dancing and singing, mushrooming in summer, tobogganing and skating in winter, sitting before a fire, eating roasted nuts and butter cakes. Because she was an unmarried young woman, her private life subject to no rules or authority, she became a subject of court gossip and, inevitably, of the empress' attention. Anna was offended by Elizabeth's frivolity, jealous of her appeal to men, nervous about her popularity and uncertain of her loyalty. At one point, Anna was so incensed by tales of Elizabeth's behaviour that she threatened to shut her up in a convent. For her part, Elizabeth understood that her status was changing when her yearly income was cut, then cut again. Anna's hostility, veiled at first, turned to personal meanness. When Elizabeth was infatuated with a young sergeant named Alexis Shubin, the empress banished him to Kamchatka, five thousand miles away. Elizabeth herself was commanded to return immediately to St Petersburg. She obeyed, taking a house in the capital and making a point by getting to know the soldiers in the Guards regiments. The officers who had served under her father and who had known her since childhood were delighted to see the last surviving child of their hero. She visited and spent time in their barracks, became familiar with the speech and habits of soldiers as well as officers, stood godmother to many of their children and soon had dazzled and conquered them.

Ironically, this much-admired young woman now found herself unable to marry. That she was the daughter and a potential heir of Peter The Great should have given her a glittering marital allure. But with Anna on the throne, Elizabeth faced insurmountable obstacles to any gilded marriage. No royal house could allow a son to pay her court otherwise this be interpreted as an unfriendly act toward Empress Anna. Elizabeth's reaction was to reject any thougt of marriage and choose freedom instead. Indeed, a man appeared whom she was to love devotedly and to whom her attachment was to be life-long.

One morning she heard a powerful new voice, a deep, rich bass, singing in the choir of the court chapel. The voice, as she discovered, belonged to a tall young man with black eyes, black hair and an appealing smile. He was a son of Ukrainian peasants, born the same year as Elizabeth at Lemeshi, a farm near Chernigov; his name was Alexis Razumovsky. In 1731, one of Empress Anna's courtiers, while passing through the village on his way back to the capital, was impressed with his vocal ability and took him to St Petersburg. The Ukrainian man was handsome which, along with his vocal talents, captivated Elizabeth, who immediately made him a member of the choir in her private chapel. And soon, he had a room near her apartment. As a favorite, Razumovsky was ideal for Elizabeth, not only because of his good looks but because he was a genuinely decent and simple man, liked for his kindness, good nature and tact. Untroubled by education, he was wholly lacking in ambition and never interfered in politics. Elizabeth loved his face, his gentle manner, his magnificent voice. Eventually he became her lover and possibly, after a secret marriage, her morganatic husband.

Another shadow fell across Elizabeth's future when, in 1730, Empress Anna brought to St Petersburg her German niece, Elizabeth Catherine Christine of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and converted her to Orthodoxy under the name of Anna Leopoldovna. Next, the empress proposed Anna Leopoldovna to marry the German prince Anthony Ulrich of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel. Anna, who was in love with someone else, refused, but the empress insisted and in the spring of 1738 the engagement was announced. The few months before her marriage saw Anna transformed from a lively, pleasant girl into a plain, silent, unhappy bride-to-be, bitterly resentful of her aunt's decision. In July 1739, Anna married Anthony Ulrich and on 24 August 1740, she gave birth to a son. Overjoyed, the empress insisted that the boy be named Ivan after her own father. Scarcely a month later, the empress suffered a stroke. However, she recovered temporarily and, in feverish haste, declared her infant grandnephew to be her heir. On 16 October 1740 Empress Anna suffered a second stroke. This time her doctors pronounced her condition hopeless and, at the age of forty-seven, she died. The following day, the two months old baby was proclaimed Emperor Ivan VI.

Ernst Johann von Biron became Regent and began his rule in a conciliatory way. He made effort to speak Russian instead of German when he appeared in public and to ingratiate himself with Elizabeth. Biron consulted her often and held conferences with her which sometimes lasted hours. Critics thought he was trying to persuade her to marry his odious elder son Peter and to use her influence with Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, now a widower, to persuade him to marry his daughter. The success in either of these directions might have secured the throne for his descendants, but if this was a plan it came to nothing.

In November 1740 Andrey Osterman, the minister of Foreign Affairs, smeared his face with lemon juice and took to his bed pretending to be ill, while Burkhard Christoph von Munnich organized a coup in favour of Ivan VI's parents. The commission appointed to try Biron's case condemned him on 11 April 1741 to death by quartering, but this sentence was commuted by the clemency of the new regent, Anna Leopoldovna, to banishment for life at Pelym in Siberia.

At first Regent Anna seemed reasonably well disposed towards Elizabeth. Elizabeth was frequently invited to the Winter Palace, however, the women were surrounded by people only too anxious to feed their fears of each other and their friendship did not prosper. Elizabeth soon became more reserved and went only for ceremonies she could not avoid. By February 1741, Regent Anna had given orders that Elizabeth be watched, however, these constraints did not escape the notice of the court and the diplomatic community. Regent Anna now surrounded herself only with foreigners. She left affairs more and more to her German advisers and spent less time on state business and more time on her coiffure and on designing an elaborate new hairstyle to be worn by the ladies of the court. Henceforth Osterman ruled Russia virtually while Anna spent her hours playing cards, chattering to her ladies-in-waiting and complaining about her husband's timidity. Anna Leopoldovna and her husband certainly seemed a contemptible couple, accusing each other of having affairs. Elizabeth did not care if Anthony Ulrich was in love with Julia Mengden, the nurse of Emperor Ivan VI, or if Anna herself was consoling with the Saxon ambassador, Carl Moritz zu Lynar, but she could not but be impressed by their incompetence.

In early autumn of 1741 Elizabeth heard rumors that Regent Anna was planning to insist that she put in writing a renunciation of her claim to the throne. A tale circulated that the regent was about to force her to become a nun and enter a convent. On the morning of 24 November, Jean Armand de Lestocq came into Elizabeth's bedroom, awakened her and handed her a paper. On one side, he had drawn a picture of her as an empress, seated on the throne, and on the other, he had depicted her dressed as a nun and behind her he had drawn a rack and a gibbet. 'Madam, you must choose finally now whether to be empress or to be relegated to a convent and see your servants persih under torture' he said. Elizabeth decided to act and, at midnight of 25 November, she set off for the barracks of the Guards. Followed by three hundred men, Elizabeth made her way through a bitterly cold night to the Winter Palace. By the time they reached the Nevsky Prospect, it was reckoned that her sledge was making too much noise, so they helped her out and she went on by foot. However, the pace was fast and they urged Elizabeth to go faster, then they took her by the arms and virtually carried her along. Walking past the unprotesting palace guards, they rushed up the staircase and along deserted corridors. Elizabeth led the way to the regent's bedroom, where she touched the sleeping woman on the shoulder. Regent Anna muttered irritably in her sleep, then her eyes blinked open and she realized immediately what had happened. There were no protests, no recriminations and no complaints. She only begged that no harm should befall her son and that her companion, Julia Mengden, be alloweed to stay with her. And Elizabeth assured her that no harm would come to any member of the Brunswick family. To the nation she announced that she had ascended her father's throne and that the usurpers had been apprehended and would be charged with having deprived her of her hereditary rights.

Karl Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp (1700-1739),

son of Frederick IV of Holstein-Gottorp and

Hedvig Sophia of Sweden

Anna Petrovna (1708-1728),

daughter of Peter The Great and Catherine I

Emperor Peter II, Peter Alexeyevich (1715-1730),

son of Alexey Petrovich and Charlotte Christine Sophia of Brunswick-Luneburg

Young Elizabeth Petrovna

by Louis Caravaque in 1720s

Alexis Gregoryevich Razumovsky (1709-1771),

a Ukrainian who rose to become lover and, eventually, the morganatic spouse of

Empress Elizabeth Petrovna

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna (1718-1746),

daughter of Karl Leopold of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Catherine Ivanovna;

Regent of Russia during her son Ivan VI's reign in 1740-1741

Ivan VI (1740-1764),

son of Anthony Ulrich of Brunswick and A

nna Leopoldovna;

Emperor of Russia in 1740-1741

Elizabeth's first act as sovereign was to shower gratitude on those who had supported her during the long years of waiting and her final coup. Each of the Gurads who had marched with her to the Winter Palace was promoted and rewarded. Jean Armand de Lestocq was made a privy councillor and physician in chief to the sovereign, besides receiving a portrait of the empress set in diamonds and a handsome annuity. He shaped Elizabeth's actions according to the advices of the French ambassador Jacques-Joachim Trotti, Marquis de la Chetardie, who was interested in toppling the regime of Anna Leopoldovna, as France sought to counterbalance the Austrian influence at the Russian court. Empress Elizabeth leant heavily on his advice in structuring her new government and it was Lestocq who recommended Alexey Bestuzhev to take Osterman's place as Grand Chancellor.

The whole shape of the administrative machine was changed as well. Elizabeth abolished the Privy Council system that had been used under Empress Anna and reconstituted the Senate as it had been under her father, Peter The Great, with the chiefs of the departments of state attending. So was the post of Procurator-General revived and Nikita Yurievich Trubetskoy was given the position. He headed the investigation and trial of Andrey Osterman and others, who were accused of ignoring Catherine I's will, proposing Elizabeth to marry a foreign prince, of persuading Regent Anna Leopoldovna to assume the title of Empress and of helping Ernst Biron to become the regent and later getting rid of him. Osterman, Munnich and eight others were condemned first to be broken on the wheel and then beheaded, but, reprieved on the scaffold, Osterman's sentence was commuted to the banishment, with his whole family, to Berezov in Siberia, where he died six years later; Munnich was sent to Pelym in Siberia, where he remained for several years, until the accession of Peter III brought about his release in 1762.

Jean Armand de Lestocq (1692-1767)

Mikhail Vorontsov (1714-1767),

a Russian statesman and diplomat

Alexey Petrovich Bestuzhev-Ryumin

(1693-1768), Grand Chancellor of Russia

In a meantime the grand prepearations had gone foward for Elizabeth's coronation. Precedent demanded that she be crowned in Moscow and in February 1742 the entire court left St Petersburg bound in that direction. During the next weeks she attended lenghty conferences to decide the forms of service to be used and the order of the entertainments. She held long discussions with her architects about how to transform dirty Moscow into a glittering capital for the day. By the dawn of 25 April Kremlin Square had been covered with the finest carpets and hung with crimson cloth. Elizabeth enjoyed every moment of the ceremony and was fervent in every response, loud in every hymn, devout in every prayer and patient throughout every sermon. There followed a round of celebrations unparalleled even by those of Empress Anna's coronation eleven years before. There were receptions galore, four masquerades within six days and another five before the end of May. There was splendid music, including exotic Turkish melodies and some splendid productions in a brand new opera house.

Elizabeth Petrovna, Empress of Russia in 1741-1762

As an unmarried and childless, now it was imperative for Elizabeth to find a legitimate heir to secure the Romanov dynasty and she chose fourteen years old Karl Peter Urich of Holstein-Gottorp. The young boy had lost his mother, Elizabeth's beloved sister Anna, when he was three months old, and his father took little interest in his infant son. The boy was handed over to nurses and at seven he began military training, learning to stand erect at guard posts, strutting about with a miniature sword and musket. Soon, he came to love the forms and atmosphere of military drill. However, Peter received a haphazard education. He mastered Swedish as well as French and learned to translate that language into German. He loved music, although his interest was not encouraged, and he delighted in playing the violin but he was never taught to play properly.

As a child, Peter was pulled in many directions. He was the heir to the dukedom of Holstein, and on his father's death he would also inherit his father's claim to the throne of Sweden. Through his mother, he was the only surviving male descendant of Peter The Great and therefore he also remained a potential heir to the Russian throne. In 1739, when Peter was eleven, his father died and the boy became Duke of Holstein. His uncle, Adolph Frederick of Holstein, the Lutheran bishop of Eutin, was appointed his guardian. Obviously, the bishop should have devoted particular care to the upbringing of young Peter who was the possible heir to two thrones, but Adolph Frederick was good-natured and lazy and he shirked this duty. The task was delegated to a group of officers and tutors working under the authority of the grand marshal of the ducal court, a former cavalry officer named Otto Brummer. The violence which Brummer inflicted on the young boy produced a pathetic, twisted child. Peter became fearful, deceitful, cowardly and cruel. He only made friends with the lowest of his servants, those whom he was allowed to strike.

Grand Duke Peter, later Peter III (1728-1762)

Empress Elizabeth Petrovna by Carle van Loo

Natalia Fedorovna Lopukhina (1699-1763),

daughter of Matrena Balk,

sister of Anna Mons and Willem Mons

Karl Peter Ulrich, later Peter III, and Sophia Augusta Frederica of Anhalt-Zerbst, later Catherine The Great

Empress Elizabeth invited her young nephew to St Petersburg, where in January 1742, in an emotional reception at the Winter Palace, she shed tears and promised to cherish her sister's only child as if he were her own. She assigned Jacob von Staehlin, an amiable Saxon, to accept chief responsibility for Peter's education. Staehlin had to adapt as best he could and he made everything as easy as possible. He exposed his pupil to the history of Russia using books filled with maps and pictures and by showing collections of old coins and medals borrowed from the art gallery. He taught geometry and mechanical sciences by making the scale models; natural science by strolling with Peter in the palace gardens to point out categories of plants, trees and flowers; architecture by taking him through the palace to explain how it was designed and built. As the boy was unable to sit quitely and listen while the tutor was talking, most of Peter's lessons were conducted with the teacher and his pupil walking side by side. Nevertheless, Staehlin was the only person in Peter's young life who made any attempt to understand the boy and handle him with intelligence and sympathy. And, although Peter learned little, he remained on friendly terms with his tutor for the rest of his life.

Elizabeth was following his progress and was always ready with encouragement for him. Observing his interest in uniforms and military parades, she at once concluded that his intellectual strength could best be developed through studying the military sciences. She had a bureau made for him crammed full of accurate working models of every conceivable instrument of war, each with a printed sheet of explanatory notes and instructions for use. But although Peter took the toys to pieces readily enough, he seemed less interested in putting them back together afterwards and the notes were never read. Elizabeth was not a patient woman; she wanted favorable result. But as the months went by and there was no improvement, her hopes were sinking. Elizabeth's principal grievance was Peter's dislike of everything Russian. She appointed teachers to instruct him in the Russian language and Orthodox religion and worked tutors and priests overtime to see that he learned. Studying theology two hours a day, he learned to babble bits of Orthodox doctrine, but he despised this new religion and felt nothing but contempt for its bearded priests.

On 18 November 1742, in the court chapel of the Kremlin, Peter was solemnly baptized and received into the Orthodox Church under the name of Peter Fedorovich. Elizabeth then formally proclaimed him heir to the Russian throne and granted him the title of Grand Duke. To make his Russian commitments irrevocable and cut off all possibility of retreat, she liquidated his claim to the Swedish throne by making it a condition of a Russian-Swedish treaty that her nephew's Swedish rights be transferred to his former guardian, Adolph Frederick of Holstein. On 23 January 1743, direct negotiations between the two countries were opened at Abo (Turku). In the Treaty of Abo, on 7 August 1743, Sweden ceded to Russia the Finnish areas east of the Kymi River with the fortress of Olavinlinna. The Swedes also agreed to elect Adolph Frederick as the crown prince of Sweden.

Late in July 1743 Elizabeth's round of pleasures was interrupted when Lestocq rushed in with the news of a plot to free Ivan VI and throw her off the throne. Within moments the palace was in a state of seige; doors were locked and the Guards rushed in. One of the chief figures involved was Natalia Lopukhina, an attractive noble woman and a rival of the empress. Her accession to the throne in November 1741 was a huge blow to Natalia and it was owing to her friendship with Anna, wife of Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin, the elder brother of Grand Chancellor Bestuzhev, that she managed to maintain her position at the court. Her affection for the exiled Karl Gustav Loewenwolde being well-known, her correspondence with this courtier was brought to light and presented to Elizabeth in the most unflattering light. Upon the further investigation, Grand Chancellor's sister-in-law, Anna Bestuzheva, was also found to be 'involved' and the Austrian ambassador, who had the instructions from Archduchess Maria Theresa to do what he could for the imprisoned Anna Leopoldovna's family. The Austrian ambassador enjoyed his diplomatic immunity, meanwhile Natalia with Anna and a number of their relatives and some associates were arrested and interrogated. The two women were publicly punished on 11 September 1743. They were brought onto the scaffold, stripped naked and flogged with birch rods and the knout. Then they had their tongues publicly torn out and were exiled to Siberia.

At this dangerous time Grand Chancellor Bestuzhev found a friend in need in Mikhail Vorontsov, who shared his political views in some way. However, his position remained delicate, especially when the betrothal between Peter and Sophia Augusta Frederica of Anhalt-Zerbst, manufactured by Lestocq and Frederick II of Prussia, took place against his will. King Frederick II was aiming to strengthen the friendship with Russia to weaken Austria's influence; Lestocq wanted to ruin Bestuzhev, on whom the empress relied and who acted in favor of Russian-Austrian alliance. A thin-lipped man with a sharp chin and broad, sloping forehead, Alexey Bestuzhev was an amateur chemist and a hypochondriac. By nature, he was moody, secretive and ruthless. A master of intrigue and, by the time he returned to power, he was so silent and efficient in wielding power that he was more feared than loved. But while merciless in dealing with his enemies, he was devoted to his country and to Elizabeth. She may have disliked the man, but she trusted him as her chief adviser and rejected all attempts of Frederick II's ambassador and agents to undermine her confidence in him.

In May 1744 Elizabeth took Peter, Sophia and Johanna Elizabeth of Anhalt-Zerbst on the piligrimage to the Troitsa Monastery. During their stay Bestuzhev presented her with the letters, which he had been busy intercepting and had discovered that not only Marquis de la Chetardie seemed to be conspiring against Russia, but that Johanna was his confidant. The empress at once descended on her and ordered her into her chambers, emerging some time later red-faced and angry. Johanna followed red-eyed and in tears. On 6 June 1744 the French ambassador was roused form his bed and ordered to pack his bags.

On 28 June 1744, Sophia was baptized into the Orthodox Church and given the name of Catherine Alexeyevna. The next day was fixed for the betrothal, followed by eight days of masquerades, fireworks and operas. And in August Elizabeth set out on a piligrimage to Kiev, the oldest and holiest of Russian cities, where Christianity was introduced by Grand Prince Vladimir in 800. The journey of almost six hundred miles between Moscow and Kiev had been suggested by Elizabeth's Ukrainian lover, Alexis Razumovsky, and the trek included Peter, Catherine and Johanna and their respective retainers. The empress and the court spent ten days in Kiev, where Catherine first saw the magnificent city in panorama, its golden domes rising from a bluff on the bank of the Dnieper River. The empress, Peter and Catherine entered the city on foot, walking with a crowd of priests and monks behind a large cross. Everywhere in this holiest of Russian cities, in a period when the church rich and the people devoutly pious, they were welcomed with extravagant pomp. No sooner had Elizabeth and the court returned from Kiev than another round of masquerades, operas and balls began in Moscow. That autumn of 1744 on her way to St Petersburg Elizabeth heard that Peter had fallen ill and the smallpox was diagnosed. She turned back immediately to Moscow and nursed Peter through it.

One of Elizabeth's priorities in 1745 was the addition of a new wing to the Golovin Palace in Moscow intended to accommodate Peter and Catherine once they were married. The empress was looking forward to the wedding with mounting excitement, even though she felt repelled by her nephew's scarred face. Peter's illness had given him an unpleasantly swollen, puffy look and left him badly pock-marked. It had also necessitated the shaving of his head and ever since he had taken to wearing a particularly large wig which made him appear even uglier and even more ridiculous.

The wedding was finally fixed for 21 August 1745 and was to take place in St Petersburg. Despite her disappointment with France, the empress decided to model it on the example the French set when the Dauphin had married the Infanta of Spain - only to make it more magnificent. On the day Elizabeth was up at dawn and, having sent for her jewel boxes, spent some time smothering her ladies-in-waiting with diamonds. After the ceremony, there followed ten days of entertainments including public masquerade, a long French comedy which lasted until three the following morning, a grand ball with fireworks and a formal supper. Everything passed off just as Elizabeth had hoped it would and now that the wedding was over, she was free to get rid of Catherine's mother. Johanna had been warned before about her intrigues and if she were allowed to stay, she might gain a dangerous influence over the grand ducal couple. In the fall of 1745 Johanna was forced to return to Germany and Elizabeth became the dominant influence in Catherine's life.

Elizabeth was nearing her thirty-sixth birthday; she remained handsome and statuesque, but she was tending to heaviness. She continued to move and dance with grace, her blue eyes remained brilliant and she still possessed a rosebud mouth. Her skin remained so pink and clear that she needed only few cosmetics. She cared immensely about what she wore and refused to put on a gown more than once. Appearing with her hair flecked with diamonds and pearls, and her neck covered with saphires, emeralds and rubies, Elizabeth created an overwhelming impression.

Nevertheless, she indulged her appetites without restraint. She ate and drank as much as she pleased. She often stayed up all night and the result - although no one dared to say - was that her beauty was fading. Elizabeth herself knew this, but she continued to live by her own rules. Instead of regularly dining at noon and supping at six, she arose and began the day whenever she felt like it. Often she postponed the midday meal until five or six in the afternoon, had supper at two or three in the morning and finally went to bed at sunrise. Until she became too heavy, she went riding or hunting in the morning and then drove out in her carriage in the afternoon. Several times a week there was a ball or an opera in the evening, followed by an elaborate supper and a display of fireworks. For these occasions, she kept changing her gowns and having her elaborate coiffure constantly reshaped.

Elizabeth went to bed reluctantly and very late. When the festivities and official receptions were over and the courtiers and guests had retired, she would sit in her private apartment with a samll group of friends. Even when these people had left her and she was exhausted, she allowed herself only to be undressed. As long as it was dark she continued to talk to a few of her women, who took turns rubbing and tickling the soles of her feet to keep her awake. Meanwhile, not far away behind the brocaded curtains of the royal alcove, a fully clothed man lay on a mattress. This was Chulkov, the empress' faithful bodyguard, who had the strange ability to do without sleep and who for twenty years had not slept in a proper bed. At last, as the light of dawn came creeping through the windows, the women would leave and Razumovsky would appear and in his arms Elizabeth would fall asleep.

The explanation for these unconventional hours was that Elizabeth feared the night; most of all she feared to sleep at night. Regent Anna Leopoldovna had been asleep when she was overthrown and Elizabeth was afraid that a similar fate might overtake her. Her fears were exaggerated; she was popular with the public and only a palace coup, organized to elevate some new pretender, could mean loss of the throne.

In the summer of 1748, Jean Armand de Lestocq was still in the high favor when he married one of Elizabeth's maids of honor - Maria Aurora von Mengden. Two months later, the newly married couple's fortune plunged. Lestocq, who continued to intrigue against Grand Chancellor Bestuzhev, was accused of plotting to dethrone Empress Elizabeth in favor of the Prussian heir to the throne. He had been interrogated and accused of sending coded letters to the Prussian ambassador and of taking bribe from the king of Prussia. Lestocq had confessed nothing and no incriminating evidence was found. Even so, his property was confiscated and he was exiled to Siberia. His disgrace was a triumph for Bestuzhev and a warning to anyone in Russia who showed any sign of favoring Prussia.

In December 1748, Elizabeth traveled to Moscow, where she would remain for a year. There, in February 1749, the empress was stricken by a mysterious stomach illness. Even though her strength eventually returned, the illness seemed to rob her of her fire. However, her sexual appetite was still strong and she meant to indulge it. In July 1749, the Shuvalov brothers arranged the meeting of their cousin Ivan Shuvalov with Empress Elizabeth, who was making a pilgrimage to the Monastery of St Sabbas. They were not disappointed in their calculations: the empress took notice of the handsome page, who was eighteen years her junior, and bid him accompany her in the pilgrimage to the Voskresensky Monastery.

Empress Elizabeth Petrovna by Ivan Argunov

Empress Elizabeth Petrovna

by Pietro Antonio Rotari

Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov (1727-1797),

son of Ivan Menshoy Shuvalov and

Tatiana Rodionovna;

the first Russian Minister of Education

Empress Elizabeth Petrovna

by Vigilius Eriksen (in 1757)

Although Ivan Shuvalov's cousins planned to use him as a pawn in their court intrigues, Ivan refused to get enmeshed in their machinations. His position grew stronger during Elizabeth's declining years and he not only made Elizabeth happy, but his enthusiasm for theatre, music and particularly for literature encouraged her to broaden her patronage of learning and the arts. Ivan was the inspiration behind the new Academy of Fine Arts and Russia's first university, soon to be established in Moscow. The French comedies were presented twice a week at the court these days, but it was at a performance of Alexander Sumarokov's tragedy Khorev, a fabulous story set in Ukraine, that Elizabeth fell in love with a handsome boy who took the leading role. The cadet was called Nikita Beketov and was promptly installed in the palace.

Alexis Razumovsky made Beketov his adjutant, which gave the former cadet the army rank of the captain. At this, the court concluded that if Razumovsky had taken Beketov under his protection, it was to counter the imperial interest being shown Ivan Shuvalov. As usual, there were sinister implications which Elizabeth did not suspect. Beketov was a pawn of Bestuzhev and it was him who arranged for the young man to be cast in the play, confident that he would appeal to the empress. Bestuzhev did not like Shuvalov's influence extending to the imperial bedroom and he was determined to put his man there instead. But though Elizabeth took Beketov to her heart, Ivan Shuvalov was not turned out as the chancellor had hoped. Indeed, not content with keeping these overs and maintaining her liaison with Razumovsky, she soon took on a fourth - a chorister named Kachenevski.

The main event during Elizabeth's last reigning years was the Seven Years' War. Elizabeth regarded the Westminster Convention (on 16 January 1756, whereby England and Prussia agreed to unite their forces to oppose the entry into, or the passage through, Germany of the troops of any foreign power) as utterly subversive of the previous conventions between England and Russia. The empress sided against Prussia over a personal dislike of King Frederick II and wanted him reduced within proper limits, so that the Prussian king might no longer be a danger to Russia. On 30 August 1756, King Frederick II's army marched into Saxony. The Prussians quickly overwhelmed their weak neighbor and then incorporated the whole Saxon army into their own ranks. Saxony was an Austrian satellite and the Franco-Austrian treaty now brought Louis XV to Maria Theresa's aid. And once Russia's longtime ally Austria was involved, Elizabeth joined Austria and France against Prussia.

Meanwhile Elizabeth was frequently ill. No one understood the exact nature of her illness, but some attributed it to complications with her menstrual periods. Others whispered that her indispositions were caused by apoplexy or epilepsy. In the summer 1756, her condition became so alarming that her doctors feared for her life. This crisis of her health continued through the autumn of 1756. The Shuvalovs, frantically worried, showered attention on the grand duke, however Bestuzhev took a different path. He was aware of the prejudices and limited political capacities of Peter, the heir to the throne, and also of the hostility that had been stirred up in Peter's mind against him as the chancellor. Now, the empress' failing health and the grand duke's hostility left him with only one figure in the imperial family to whom he might turn for support. His relationship with Catherine had strengthened and the approach of war speeded their rapprochement. By the autumn of 1756, Bestuzhev was deeply concerned about the transition of power that would follow Elizabeth's death.

In June 1757, a new French ambassador, Paul Francois Galluccio, Marquis de l'Hopital, had arrived to set about his mission of strengthening the French ties with Russia. He began by pressing for the English ambassador's recall to England and Stanislaw Poniatowski's, then Catherine's favorite, return to Poland. He was warmly received by the Shuvalovs, but he was rebuffed at the young court. Nevertheless, the French ambassador did manage to achieve a major goal: he succeeded in getting rid of his English diplomatic rival. He and his government pressed Elizabeth to force the recall of an envoy whose king, they pointed out, was now an ally of their mutual enemy, Frederick II of Prussia. Elizabeth accepted this logic and, in the summer 1757, George II of England was informed that his ambassador's presence was not desired in St Petersburg.

Russia, bound by her alliance with Austria, had been nominally at war with Prussia since September 1756, when Frederick II invaded Saxony. By late spring of 1757, however, not a single Russian soldier had marched. No money had been spent on the army and the troops were badly trained and poorly equipped. Morale was low, not only because Elizabeth had promised to send this army against Frederick II, the foremost general of the age, but also because the empress' declining health meant that the Russian crown might soon be placed on the head of a young man who was Frederick II's fervent admirer.

In May 1757 red-faced field soldier, Stepan Apraksin, physically unable to mount a horse, climbed into his carriage snd set out for East Prussia at the head of eighty thousand men. At the end of June, the army seized the fortress of Memel, on the Baltic coast. On 17 August Apraksin defeated a part of the Prussian army in a battle at Grossjagersdorf. Instead of following up his victory by advancing into East Prussia and capturing Konigsberg, Apraksin remained motionless for two weeks, after which he turned around and retreated by forced marches so precipitous that his withdrawal appeared to be a rout. The general burned his wagons and ammunition and burned villages behing him so they could provide no shelter for a pursuing enemy. He halted only when he reached the safety of the fortress of Memel. This retreat provoked angry complaints from the Austrian and French ambassadors in St Petersburg. Bestuzhev was alarmed, because Apraksin was his friend and had received command of the Russian army from him, the chancellor knew that he would bear a share of blame.

Meanwhile, St Petersburg was a cauldron of recrimination. Empress Elizabeth, pressed by the Shuvalovs and the French ambassador, relieved General Apraksin of his command and sent him to one of his estates to await for the investigation. General Wilhelm Fermor took over the army and, despite bad weather, moved forward and seized Konigsberg on 18 January 1758. Fermor also tried to clear his predecessor by pointing out that, through no fault of General Apraksin's, the Russian soldiers had not been paid, that they were short of ammunition, weapons and clothing. With endurance and courage, they had defeated the Prussians at Grossjagersdorf, but the effort had proved too much and General Apraksin, unable to supply his troops in enemy territory, had been compelled to retreat.

A year after his dismissal, in August 1758, Apraksin was brought before a judge to receive his sentence. The general, overweight and apoplectic, never heard the end of the judge's sentence. Expecting the words 'torture' and 'death', he fell dead on the floor. The judge's last words were to have been 'to set him free'.

The cowardice and incapacity of his friend, Stepan Apraksin, after winning the Battle of Grossjagersdorf, became the pretext for overthrowing the chancellor. Elizabeth ordered a meeting of the war council on 14 February 1758. The chancellor was summoned, but ever sensitive to the political climate, he sent word that he was ill. His excuse was rejected and he was ordered to come immediately. Bestuzhev obeyed and, upon arrival, he was arrested. His titles and orders were stripped from him and he was sent back to his house a prisoner - without anyone troubling to tell him of what crimes he was accused. However, no evidence was produced and the former grand chancellor was exiled to one of his own estates where he remained until, three years later, Catherine became an empress.

Neither the serious illness of Elizabeth, which began with a fainting fit at Tsarskoe Selo, nor the fall of Bestuzhev, nor the intrigues of the various foreign powers at St Petersburg, interfered with the progress of the war and the crushing defeat of Kunersdorf on 12 August 1759 at last brought Frederick II to the verge of ruin. From that day forth he despaired of success, though he was saved by the jealousies of the Russian and Austrian commanders, which ruined the military plans of the allies.

Elizabeth sensed that Grand Duke Peter was waiting impatiently for her death, but she was too exhausted to carry out her real wish and transfer the succession to Paul. She had energy and focus enough only to drag herself from her bed to a sofa or an armchair. Ivan Shuvalov was no longer able to comfort her and she seemed at peace only when Alexis Razumovsky, her former lover and perhaps her husband, was sitting by her bed, soothing her with soft Ukrainian lullabies. As the days passed, Elizabeth lost interest in Russia's future and took less interest in her surroundings. She knew what was coming and her agony paralyzed Europe. All eyes were on the sickroom, where the outcome of the war hung on the struggle of a woman fighting for her life. The allies' hopes near the end of 1761 was that the empress' doctors might manage to prolong her life for another six - and, if possible, twelve - months, by which time they hoped that Frederick II of Prussia would be beyond recovery.

By the middle of December 1761, everyone knew that the empress would die soon. On 23 December, Elizabeth had a massive stroke. The doctors gathered around her bed agreed that this time there would be no recovery. The empress asked Peter to promise to look after little Paul. Peter, aware that the aunt who had made him her heir could also unmake him with a single word, promised. She also charged him to protect Alexis Razumovsky and Ivan Shuvalov and, on Christmas Day, 25 December 1761, near four o'clock in the afternon, Elizabeth died. That night, while Alexis Razumovsky, sick with grief, shut himself up in his rooms, the new emperor gave a grand supper party in the hall adjoining the chamber in which the body lay. The funeral took place on 25 Janaury 1762.

After Elizabeth's death Alexis Razumovsky submitted his resignation and moved from the Winter Palace to Anichkov Palace, which had been gifted to him by Elizabeth. After Catherine II's accession to the throne, Razumovsky refused the title of highness that was offered to him and at her request he destroyed all recorded documents of his marriage with Elizabeth. Razumovsky died on 6 July 1771 in St Petersburg.

Stepan Fedorovich Apraksin (1702-1758),

Field Marshal who commanded the Russian armies during the Seven Years' War